For millions of years, our ancestors preferred to hunt the largest available animals, leading to the extinction of megafauna. The resulting food energy was more rewarding for the effort involved. Early humans also burned biomass and transformed the landscape to suit their needs, and as the first cities rose, so did widespread deforestation.

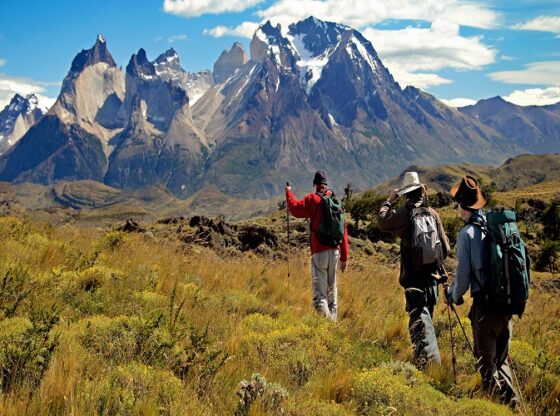

Reality is different, however. You don’t go halibut fishing solely to feed your family but as a challenge, a part of a greater outdoor experience. Tourists visiting the wilderness are a boon for the local economy, but supporting such activities requires building infrastructure.

Even though we farm or process most of our dietary needs and draw upon renewable energy sources, the tension between man and nature continues to exist. Often, it draws a line through society. People can’t seem to agree on whether this is good or bad.

Table of Contents

The way we approach wilderness tourism and its associated activities can change that.

Primal behaviors

Small populations of hunter-gatherers continue to exist today in remote areas around the world. Many homesteaders have to worry about wild animals threatening their livestock or ruining their produce. In both scenarios, killing wildlife can be framed as a necessary act of survival performed by people who live in the context of frontier existence.

But throughout history, and even today, people also kill animals, particularly big game, for sport. The practice raises controversy, drawing accusations of excessive consumption.

However, this isn’t a simple, black-and-white affair. It’s actually rooted in a primal drive to prove one’s capabilities and thereby earn greater status among one’s tribe. And in most developed countries, sport hunting and angling are carried out under strict regulations. You might only be allowed to hunt certain species in season, and only if you’re registered and stick within a quota.

Similar principles drive those of us who shoot with cameras instead of guns. Many people going on outdoor adventures subsequently post their pictures to social media. Unwittingly, they’re doing so for the status boost of getting likes and engagement from their peers.

Potential for positive impact

We’re driven by this primal craving for status, yet mostly unaware of it. Tourists seldom frame their activities regarding personal status benefits versus the cost of such intrusions into the natural balance.

However, some bigger stakeholders do think in those terms. Regulatory bodies, such as those overseeing hunting or forestry operations, must weigh the pros and cons of allowing such activities. It’s easy to see only the negative impacts, but there are arguments in favor of our continued impositions on the wilderness environment.

The funds generated by tourism can be funneled towards local conservation efforts. While some areas must give way to roads and lodgings, more vital spots will benefit from increased resources allocated to habitat preservation and ecosystem restoration.

In areas where illegal hunting is a problem, the presence of tourists acts as an additional deterrent. Many tourists are also wildlife enthusiasts or citizen scientists who can help observe, gather data, and monitor the ecosystem’s vitality.

A strong tourism-based local economy creates sustainable livelihoods and raises community support for conservation, leading to better protective policies. It works both ways, as tourists come away from their experience with a genuine appreciation of the need for sustainability. Instead of posting about their adventures for likes and follows, they do so to spread greater awareness through the online community.

Striving for information and cooperation

However, for all of that to happen, we need fluent cooperation and for everyone to continue striving to be better informed.

Ecosystems are sensitive to the smallest change, and in the modern era, no area remains untouched by human activity. It’s illogical to think that we can somehow preserve wilderness areas unspoiled. Rather, emphasis should be placed on the quality of our interactions with the environment.

In a study of northern countries where hunting tourism is popular, it was found that this activity could be sustainable. However, the participants have to make ecological sustainability a core value. Stronger social engagement between interest groups, including hunters, local landowners, tourist companies, and indigenous people, is also a must to resolve conflicts and achieve a compromise that suits all.

As tourists from the younger generations continue to be motivated by authentic natural experiences, we need to be pragmatic. Humans will continue to shape the environment and indulge in the primal desire to hunt. We have the opportunity to change our attitudes and motivations behind these actions and ensure that we’re doing them responsibly and sustainably. That way, everyone, including future generations, can hope to enjoy the same experiences.